What is Vipassana Meditation? Insights from the Thai Forest Tradition

In the West, vipassana meditation is often closely associated with the famous 10-day retreats popularized by S.N. Goenka. While Goenka’s method has introduced many to this profound practice, vipassana is much broader, with living traditions rich in diversity and depth.

One such tradition is the Thai Forest Tradition vipassana, rooted deeply in the original teachings of the Buddha and transmitted by revered Thai forest monks. This tradition emphasizes flexibility, adapting practice methods to each individual practitioner, guided by the four foundations of mindfulness (Satipaṭṭhāna).

This article aims to introduce the Thai Forest approach to vipassana meditation, offering insights into its unique features and practical ways of practice. It is a humble sharing for all meditators — whether beginners or experienced, followers of Goenka’s retreats, or those curious about different paths.

What is Vipassana? A Brief Canonical Foundation

The Pāli word vipassana means “clear seeing” or “insight.” It refers to seeing reality directly as it is — recognizing the three universal characteristics of existence:

- Impermanence (anicca)

- Suffering or unsatisfactoriness (dukkha)

- Not-self (anattā)

The Buddha taught the practice of vipassana primarily through the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta (Foundations of Mindfulness), which outlines four foundations for cultivating mindful awareness:

- Kāyānupassanā — mindfulness of the body

- Vedanānupassanā — mindfulness of feelings or sensations

- Cittānupassanā — mindfulness of the mind or mental states

- Dhammānupassanā — mindfulness of mental objects or principles

The Thai Forest Tradition in Brief

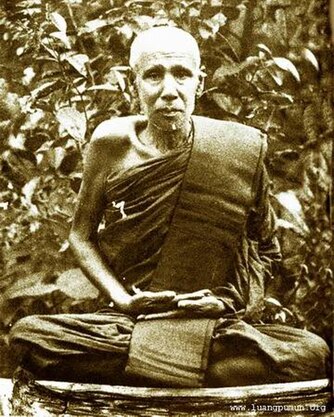

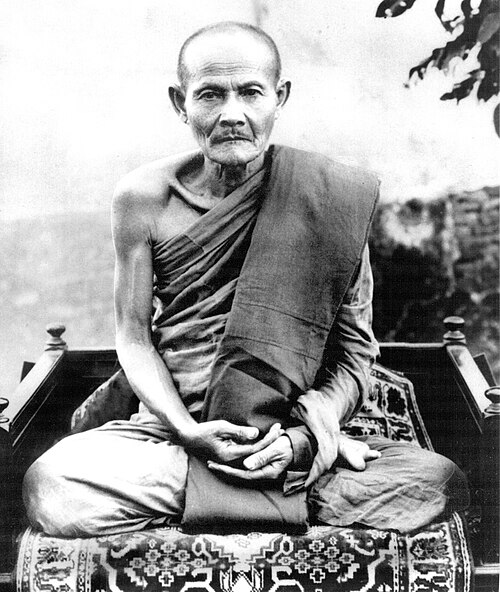

Ajahn Sao Kantasīlo(left) and Ajahn Mun Bhuridatto (right), founders of the Kammaṭṭhāna Forest Tradition of Thailand lineage.

The Thai Forest Tradition arose as a reform movement within Theravāda Buddhism during the early 20th century, led by masters such as Ajahn Mun Bhuridatto and Ajahn Sao, and later shaped by luminaries like Ajahn Chah, Luang Pu Dune Atulo, Luang Ta Maha Bua, Luang Pu Thate Desaransi, and other prominent monks in the Ajahn Mun lineage. This tradition emphasizes:

- Returning to the simplicity and rigor of the Buddha’s original monastic life, often in natural, forested settings

- Integration of samatha (calm/concentration) and vipassana (insight) practices

- Flexibility in method, tailored by teachers according to the temperament and circumstances of each student

- Direct experience over rigid formulas

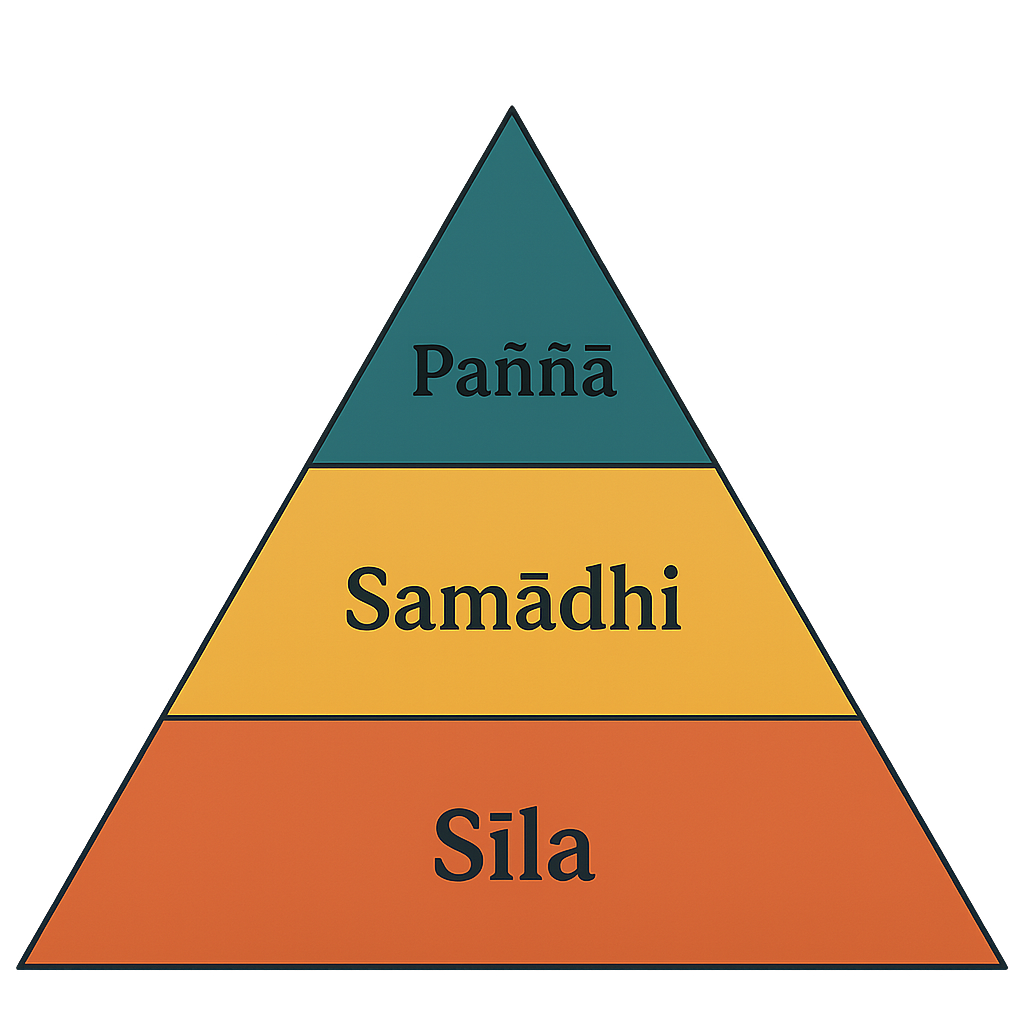

Foundations of Practice: Sīla, Samādhi, and Paññā

The Thai Forest Tradition emphasizes that vipassana does not arise in isolation. Its practice is grounded in three essential foundations:

- Sīla (morality): Ethical conduct and restraint, creating a stable mind free from remorse and agitation.

- Samādhi (concentration): Developing calm and focused awareness through meditation objects like the breath, supporting insight.

- Paññā/Puñña (wisdom/merit): Insight into impermanence, suffering, and not-self, cultivated alongside virtuous actions.

These three pillars form an integrated path: ethical living stabilizes the mind, concentration deepens insight, and wisdom guides the practitioner toward liberation.

Satipaṭṭhāna 4 as a Working Framework in the Thai Forest Tradition

Unlike some fixed retreat styles, the Thai Forest Tradition uses the four foundations of mindfulness (Satipaṭṭhāna 4) not as a checklist but as a flexible framework. Forest monks and teachers select which foundation or “door” to emphasize based on the student’s nature:

- Some may start primarily with body mindfulness (kāyānupassanā), contemplating the body’s impermanence and unattractiveness (asubha) to develop detachment

- Others focus on mindfulness of feelings (vedanā) or mind states (cittā)

- Teachers guide meditators to develop clear, continuous awareness tailored to their progress and challenges

Key Teachers & Their Teachings

- Ajahn Mun Bhuridatto emphasized strong concentration (jhāna) as the foundation supporting vipassanā insight.

- Luang Pu Dune Atulo recommended starting with “bare awareness” of the mind (cittānupassanā), which may not require long sitting or deep jhāna, especially suitable for modern practitioners.

- Luang Por Chah Subhaddo (Ajahn Chah) taught the inseparability of calm and insight, encouraging mindfulness of present experience with simplicity.

- Luangta Maha Bua Ñāṇasampanno placed strong emphasis on unwavering mindfulness and intense investigation of the mind itself, using deep concentration to penetrate the “original mind” and uproot subtle defilements. He taught that wisdom must be sharp and relentless, probing reality until all clinging ceases.

- Luang Por Wiriyang Sirintharo promoted a step-by-step meditation system, starting with sustained concentration and then transitioning into clear insight. He emphasized consistent daily practice and the idea that anyone, regardless of lifestyle, can develop vipassanā if they maintain steady mindfulness in all activities.

- Luang Pu Sim Puttajaro highlighted gentle but continuous awareness, encouraging practitioners to let go of forceful striving and instead maintain a relaxed, open attention. He stressed that wisdom naturally arises when the mind is calm, clear, and unattached to results.

- Other teachers in the lineage contributed important perspectives enriching the tradition’s adaptability.

Practical Ways of Practicing Vipassana

In the Thai Forest Tradition, Vipassana is taught through multiple skillful methods, adapted to each practitioner:

- Samatha-first, then Vipassana: Develop strong concentration on an object such as breath, the mantra Buddho, or a kasina. Once the mind is calm, turn awareness toward insight into impermanence, suffering, and not-self. (Ajahn Mun)

- Vipassana integrated with Samatha from the start: Calm and insight arise together without waiting for deep jhāna. Observe sensations, feelings, and thoughts in real time. (Ajahn Chah)

- Body Contemplation (Kāyagatāsati): Use the body as the main object; contemplate parts, decay, death, impermanence, and movements. (Ajahn Lee, Ajahn Mun)

- Contemplation of the Mind (Cittānupassanā): Watch the mind’s moods, intentions, and mental states arise and pass without clinging or aversion. (Ajahn Maha Bua)

- Cittānupassanā as taught by Luang Pu Dune Atulo and Luang Pu Pramote Pamojjo: Dune: Awareness of the mind itself, recognizing distractions and returning to the “knower.” Pramote: Use a meditation anchor (breath, mantra, posture) to notice mind movements; insight unfolds naturally.

- Direct Awareness of the Three Characteristics: Observe impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and not-self in all phenomena. (Ajahn Chah)

- Daily-life Vipassana (Continuous Mindfulness): Apply insight to walking, working, eating, and speaking. “The forest is not just trees — it’s your own heart.”

The Thai Forest Tradition vipassana offers a living, adaptable lineage grounded in the Satipaṭṭhāna 4, inviting practitioners to find their own path. Whether focusing on body, sensations, or mind, with patient guidance, deep insight is possible. Exploring mindfulness of mind states (cittānupassanā) may open new doors without requiring prior jhāna. Both forest and Goenka methods offer rich, complementary paths.

May this humble introduction inspire curiosity and heartfelt practice on the journey toward awakening.

References

- Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu (trans.). A Heart Released. Metta Forest Monastery, 2005.

- Luang Pu Dune Atulo. Gifts He Left Behind. Trans. Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu, 2006.

- Ajahn Chah. Food for the Heart. Wisdom Publications, 2002.

- Ajahn Chah. Being Dharma: The Essence of the Buddha’s Teachings. Shambhala Publications, 2001.

- Luang Pu Pramote Pamojjo. The Correct Practice of the Dhamma. Thailand, 2010.

- Maha Bua Ñāṇasampanno. Arahattamagga Arahattaphala: The Path to Arahantship. Wat Pa Ban Tat, 1997.

- Wiriyang Sirintharo. Samādhi and Vipassanā. Dhammachai Foundation, 2014.

- The Life and Teachings of Luang Pu Sim Puttajaro. Thailand, 2010.

- Ajahn Lee Dhammadharo. Keeping the Breath in Mind & Lessons in Samādhi. Metta Forest Monastery, 1980.

- Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu & Bhikkhu Bodhi (trans.). The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha. Wisdom Publications, 1995.

- Walshe, Maurice (trans.). The Long Discourses of the Buddha. Wisdom Publications, 1995.

- Tiyavanich, Kamala. Forest Recollections: Wandering Monks in Twentieth-Century Thailand. University of Hawai‘i Press, 1997.